I would rather be talking about real things. Since September 2011, northern Mali has been on tenterhooks, waiting to see which rumors of risings, rebellions, independence struggles or gang-war will pan out. Yet I am hesitant to even write anything on the situation. I see quite clearly how those living in Kidal and Tombouctou themselves seem unsure as to who has been doing what, and even less clear on what is planned by the bulging troupe of demobbed Libyan soldiers, ex-rebels, competing local and national power networks, criminal gangs, militaries of four countries, freedom fighters, and armed salafists.

Cue Jeremy Keenan. Keenan fears nothing. He has one answer for all questions, one bad guy and one bad guy only who is behind all disorder and suffering. Scholarly rigor and any critical sense are cast aside. Keenan’s strange status — he is a “Professorial Research Associate in anthropology” who apparently does not teach classes or publish scholarly work — at School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London seems to give weight enough to see his pieces published in otherwise reputable outlets. Al Jazeera has printed a number of Keenan’s pieces, although at some point in mid 2011 they wisely moved his work from News to “Opinion”.

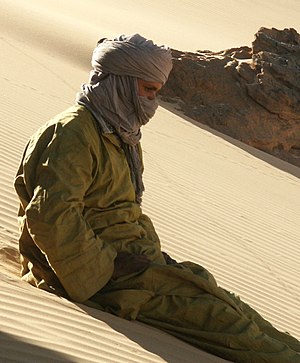

People who don’t know much about northern Mali would be very poorly served by reading Keenan’s increasingly odd writing. Keenan used to be a scholar of some note. His 1977 book remains the best English language text on the Ahaggar Touareg of southern Algeria. But over the last decade or two his writing has descended into screed. His 2004 collection of articles, published as “The lesser gods of the Sahara: social change and contested terrain amongst the Tuareg of Algeria”, seems his last work with any scholarly pretensions, with a dozen articles and two books since rehashing the same mix of speculation and a shallow version of anti-imperialism. And while I like a good kick against the pricks as much as the next person, his writing has also increasingly lost any critical rigor it once had. All that remains is a sort of mono-maniacal invective against the Algerian DRS. They are a good target: the Directorate of Intelligence and Security have at least as much blood on their hands as any secret police of any authoritarian state. But the increasingly unhinged supposition that their hidden hands are behind all that is bad in the west-central Saharan region is simply unsupportable. As importantly, it lets some equally bad actors off the hook. It also reduces all Touareg (who prefer the label “Kel Tamasheq” by the way), Arabs, Songhai and other people who make their homes there, to deculturated, classless, ahistoricised puppets. As many people, I had seen Keenan stumble down this unfortunate path for some time. But I never though I would hear him reconfigure the traumatic Tuareg insurgencies of the 1990s and 2000s and their leaders as window dressing for elaborate foreign plots.

And yet here we are, facing Keenan’s most recent work “A new crisis in the Sahel”, which appeared on Al Jazeera English January 3rd. Despite its title, there is nothing “new” here. New events are — in Keenan’s writings — simply another manifestation of a single conspiracy. This nefarious plot involves the Algerian state, the CIA, and literally no one else. They have invented and pay off a “terrorist” group to allow some sort of power grab by Algeria, and extension the United States. This ignores the obvious fact that the United States political elites, along with some on the Israeli right, are much closer to Algeria’s arch-foe Morocco. To read Jeremy Keenan is to know that it is here, in the midst of the Saharan desert, that a great game is being played out, in which invented armed groups pose for cameras and fight no one but sacrificial victims arranged by their handlers. Pain and suffering in the Sahara exists solely to influence the popular press in the United States, Europe and Algeria. It is essentially all for our benefit. And God knows, there is nowhere like the desert 600km north of Tombouctou to stage events which will demand the attention of American newsreaders.

When Keenan began this trip in 2003-4, his take was more plausible. Al-Qaida au Maghreb islamique (AQMI) was still the Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (GSPC), and US spy satellites were tracking a small band of GSPC kidnappers from their homes in Algeria across much of the Sahara. Keenan was good at stating the obvious, missed by much of the press. The Algerian civil war bred unknowably complex corruption and relationships between Algerian power and its opponents. The United States military and government was keen to portray all conflict as part of its global obsession with Osama Bin Laden, no matter how contrived the links. Easily understood enemies bolstered both political powers just as it funded security services with slick appropriation pitches in Washington and backhanders from smugglers in Tamanrasset or Tindouf. By 2005 this simple linkage has overtaken all of Keenan’s former work. His writing is now almost entirely about this ever deepening, ever more complex conspiracy, the tentacles of which Keenen discovers everywhere. Every conflict, every actor must be hammered into this template. And while his work has slid from the finest academic journals into the popular press and a single journal to which he has some connection, his invitations to cocktail parties thrown by Algeria’s equally repugnant regional rivals have no doubt increased.

Might we not do better consulting other prominent scholars or (gasp) actual Malians, Nigeriens or Algerians? One consequence of Keenan’s writing is that it increasingly removes all agency, motivation, and history from Africans, replacing them with mere puppets of unseen foreign forces. While the DRS or AFRICOM have dark motives, the events he sloppily half describes in Al-Jazeera have much more to do with an actual history of a region torn by the after-effects of European colonialism, rentier-state neo-colonialism, multi-sided regional struggles (in which I suspect Keenan of having some interest), poverty, and ill-governance.

On the level of fact (for instance who Iyad Ag Ghali is and his local/national/regional ties) Keenan privileges rumor over history. And sometimes he departs from history altogether. The portrayal of the 2006 insurgency as a one day affair orchestrated by a foreign government is simply inaccurate, and the failure to mention other factions — such as those led by the late Ibrahim Ag Bahanga or the more conservative Abdoussalam ag Assalat — seem calculated by Keenan to paper over the gaping holes his statements leave. For his citation of a Le Journal du Dimanche article claiming Ag Ghali orchestrated the Hombori kidnaps, there are ten others — citing better informed sources than one anonymous Nigerien security officer — that speculate the opposite. It’s as if he read but one of the hundreds of press reports. Except that sheer poor research would hardly result in finding the single article that speculates in Keenan’s direction. Anyone following these events (again, maybe an actual African!) would tell you this immediately.

Example: why never a mention of French interests? Total just scored a large oil prospecting bloc in the Mauritanian Taoudeni basin just across the border which promises the first oil and natural gas wells in the region. Or French air and ground assets spread from Niamey to northern Burkina to Gao? Or that the Hombori kidnappees were formerly French mercenaries and political fixers for African elites close to Paris? Why not mention the communal conflicts bred of competing nationalisms, bitter caste and class histories, and the deformed half democracy of local governments? Why not mention the affiliations of the former Libyan officers or their history in the 1990s insurgency? Why not mention the extensive interlinked and competing smuggling networks of both local notables and rich men based in Bamako or Tamanrasset? Why not mention AFRICOM’s much longer involvement with Bamako than Algiers? Why not mention the fact that for the third time in six years, many desert side communities in the region are facing famine rooted in environmental degradation, disappearance of forage for herds, and price spikes driven by foreign food trade and market specualtion. These problems are real. They are complex. And they involve shades other than black and white, players unknown to most Europeans or Americans.

Keenan reduces a complicated living history and society to the maneuvers of the Algerian secret police and the CIA. Those are not nice or well intentioned people: no doubt. But the CIA and Algeria’s secret police are easily understandable by western readers. It paints a world of binary conflicts, with simple motivations, focused on Western elites and their concerns. Perhaps this is comforting for his foreign reader, but it is also a narrative that removes several million Africans from their own history, as if they all simply take orders from other white folks with whom Keenan has a beef. And I see nothing either liberating or accurate in any of it.

A Sample of Keenan’s recent work

- A new crisis in the Sahel – Opinion – Al Jazeera English

- The Dying Sahara: US Imperialism and Terror in Africa Pluto Press, 2012 ISBN 0745329616

- The dark Sahara: America’s war on terror in Africa. Pluto Press, 2009 ISBN 0745324525

- Africa unsecured? The role of the Global War on Terror (GWOT) in securing US imperial interests in Africa – Critical Studies on Terrorism – Volume 3, Issue 1 Volume 3, Issue 1, 2010

- Al-Qaeda terrorism in the Sahara? Edwin Dyer’s murder and the role of intelligence agencies – Keenan – 2009 – Anthropology Today

- US Militarization in Africa: What Anthropologists Should Know about AFRICOM. Anthropology Today, Vol. 24, No. 5 (Oct., 2008), pp. 16-20

- Uranium Goes Critical in Niger: Tuareg Rebellions Threaten Sahelian Conflagration – Review of African Political Economy – Volume 35, 2008

- The Banana Theory of Terrorism: Alternative Truths and the Collapse of the ‘Second’ (Saharan) Front in the War on Terror – Journal of Contemporary African Studies – Volume 25, Issue 1

- US Silence as Sahara Military Base Gathers Dust, Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 34, No. 113, Imperial, Neo-Liberal Africa? (Sep., 2007), pp. 588-590

- Conspiracy theories and ‘terrorists’: How the ‘war on terror’ is placing new responsibilities on anthropology . Anthropology Today, Volume 22, Issue 6, pages 4–9, December 2006

- The making of terrorists: Anthropology and the alternative truth of America’s ‘War on Terror’ in the Sahara. Focaal, Volume 2006, Number 48, Winter 2006 , pp. 144-151(8)

- Turning the Sahel on Its Head: The ‘Truth’ behind the Headliness. Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 33, No. 110, Religion, Ideology & Conflict in Africa (Sep., 2006), pp. 761-769

- Military Bases, Construction Contracts & Hydrocarbons in North Africa. Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 33, No. 109, Mainstreaming the African Environment in Development (Sep., 2006), pp. 601-608

- Ray Bush and Jeremy Keenan. Editorial: North Africa: Power, Politics & Promise, Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 33, No. 108, (Jun., 2006)

- Tuareg Take up Arms. Review of African Political Economy Vol. 33, No. 108, North Africa: Power, Politics & Promise (Jun., 2006), pp. 367-368

- Security & Insecurity in North Africa Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 33, No. 108, North Africa: Power, Politics & Promise (Jun., 2006), pp. 269-296

- Famine in Niger Is Not All That It Appears. Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 32, No. 104/105, Oiling the Wheels of Imperialism (Jun. – Sep., 2005), pp. 405-407

- Waging war on terror: The implications of America’s ‘New Imperialism’ for Saharan peoples – The Journal of North African Studies – Volume 10, Issue 3-4 2005

- Political Destabilisation & ‘Blowback’ in the Sahel. Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 31, No. 102, Agendas, Past & Future (Dec., 2004), pp. 691-698

- Terror in the Sahara: The Implications of US Imperialism for North & West Africa. Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 31, No. 101, An African Scramble? (Sep., 2004), pp. 475-496

- Americans & ‘Bad People’ in the Sahara-Sahel Americans & ‘Bad People’ in the Sahara-Sahel, Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 31, No. 99, ICTs ‘Virtual Colonisation’ & Political Economy (Mar., 2004), pp. 130-139

6 comments for “Death and Career in the “Dark” Sahara: The Sad Fate of Jeremy Keenan”